By Amber Strong ’89 Makaiau

A number of our authors have written about a progressive education approach to curriculum design over the years, but surprisingly, it is hard to find progressive education writers that focus on lesson planning. For example, in this post I give a brief introduction to the history of progressive education curriculum design, then highlight Hanahau‘oli School’s approach to developing “integrated, interdisciplinary, and thematic” units of study. In Gabby Holt’s blog about concept-based learning, she emphasizes unit planning and the ways progressive education units based on concepts rather than topics can cultivate and build students’ enduring understandings over time. Other bloggers, like Brett Peterson who published the incredible read, “Uncovering The Progressive Past: The Origins of PBL,” underscores the progressive education movement’s role in introducing educators “to a curriculum inspired by and designed with the project,” also known as project-based learning (PBL). In each of these pieces, it is clear that the progressive education tradition favors longer-term units of study or projects as the foundation for curriculum design, rather than shorter lessons or discrete lesson planning.

So where does lesson planning fit into a progressive philosophy and pedagogy? In this blog, I begin by digging into the reasons progressive educators might tend to focus on long-term unit or project planning, rather than individual lessons. Next, I’ll share a progressive education lesson plan template that I had my Progressive Philosophy and Pedagogy Master’s students experiment with last semester. This will include sharing a few of the lessons they developed, and how I observed them applying the defining features of a progressive philosophy and pedagogy to designing shorter lessons. I’ll conclude with some final thoughts, reminding us all that curriculum design and planning is only part of the equation in delivering a high-quality progressive education.

Why the Focus on Units or Projects, Rather Than Lesson Plans?

The overall philosophy underlying most progressive educators’ tendency towards focusing on the “backwards design” (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005) of longer-term units of study–where each day of learning holistically builds on the one that came before it–is grounded in the core progressive education idea that “facts and skills do matter, but only in a context and for a purpose. That’s why progressive education [curriculum design] tends to be organized around [big conceptual] problems, projects, and questions [which frame extended investigations or inquiries], rather than around lists of facts, skills, and separate disciplines [that are often taught in short, standalone, fragmented, and unrelated lessons]” (Kohn, 2015, p. 3). As Kohn (2015), points out, “consistent with the overwhelming consensus amongst experts that learning is a matter of constructing ideas rather than passively absorbing information or practicing skills” (p. 3), progressive educators value student-centered approaches where learners actively build knowledge through meaningful experiential learning that will be remembered over time, rather than passively receiving information for short-term knowledge acquisition that they are accountable for on school quizzes and tests.

This was the philosophy of progressive education heavyweight, William Kilpatrick. Kilpatrick was a student of John Dewey’s, and is credited with coining the term “Project Method” (1918), which was his overall approach to progressive education curriculum design. Project-based learning, he explained, “should represent a wholehearted purposeful activity of the worthy life in a democratic society, and thus the project or purposeful act is considered as life itself and not preparation for later living” (Pecore, 2015, p. 158). Today, thanks to Kilpatrick, the PBL approach has become–“a systematic teaching method that engages students in learning knowledge and skills through an extended inquiry process structured around complex, authentic questions and carefully designed products and tasks” (Markham, Larmer & Ravitz, 2003, p.4)–that is used to create progressive education curriculum across the globe.

Herein lies some of the reasons progressive educators tend to give their time and attention to designing larger units of study or projects, rather than daily lessons. But does this mean lesson planning should be ignored by progressive educators? The answer is no, and here are some of my reasons. First of all, larger units of study or projects must be broken down into smaller parts, especially if they have to fit within the structures of a traditional school day (e.g. blocks of time that are pre-planned for particular activities within a daily schedule). Second, sometimes standalone, short, or discrete lessons need to be taught. This could be a particular skill that will be applied in multiple units or projects (e.g. creating a reference list for a research project) or a one-off lesson that is responding to a current event or unscheduled teachable moment (e.g. the caterpillars are turning into a chrysalis on the crown flower tree right outside your classroom). In all of these cases, it is important that progressive educators learn how to apply the same philosophy and core elements, used to design large units of study or PBL, to shorter-term learning experiences within those same units and projects.

Experimenting with a Progressive Education Lesson Plan Template

In Fall 2025, I experimented with introducing the students in our Progressive Philosophy and Pedagogy Master’s program with a progressive education lesson plan template that Dr. Chad Miller and I had designed during the first cohort of the program. The students were taking Cultural Diversity and Education as a part of their required coursework, and one of the class assignments invited them to work with a team of three to design a social justice lesson plan to teach in one of the seminar sessions. They were asked to use THIS PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION LESSON PLAN TEMPLATE. Other criteria included making sure their lesson plans were designed using a progressive pedagogy and focused on teaching a social justice topic or resource from the Social Justice in Education: Theory to Practice website (a resource that we were using throughout the course). They were also provided with this ASSESSMENT CHECKLIST, which I used to give them feedback on their design prior to teaching the lesson, as well as a narrative evaluation after the lesson was taught.

If you take a look at the lesson plan template, you will see that it is pretty minimal. However, as my students started designing and teaching their lessons, they instinctively applied a number of additional elements of progressive philosophy and pedagogy to the curriculum design process. For example, 100% of the students used a constructivist framework to scaffold student learning experiences throughout the lesson, much in the same ways they had been taught to develop a progressive education unit plan. In the context of lesson planning, it looked like this:

Starting with what students already know

Presenting new information/concepts in an effort to deepen and expand what they know

Structuring time to practice applying the information/concepts to relevant resources or experiences

Providing opportunities for students to engage in experiential exploration, creativity, construction and integration, and eventual application of new knowledge into their already existing knowledge

Ending with reflection on what they learned

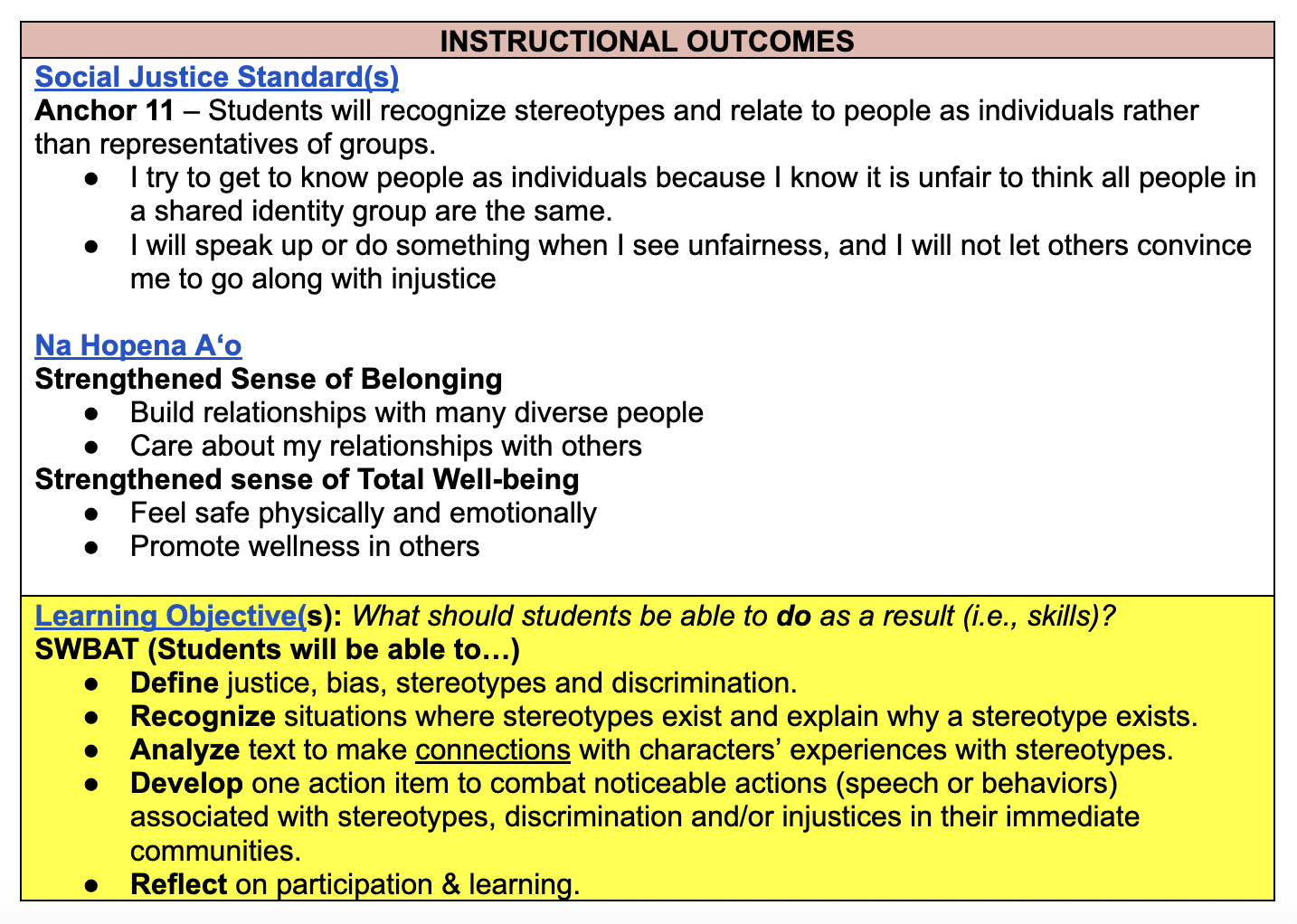

Below is an example of what this looked like in the “Learning Objectives” listed in a lesson plan designed by Dwayne Sakaguchi Jr. and Keenan Lau.

As you can see, Dwayne and Keenan modeled the successful application of constructivist principles of teaching and learning to design the lesson’s objectives and eventually teach this progressive education lesson plan.

A similar application of progressive education principles to lesson planning can also be seen in the narrative feedback I gave to Caitlin Gonzales and Eugene Marquez after they finished teaching their lessons for the same assignment. The complete assessment checklist that contains my evaluation and narrative feedback can be found here, but some of my comments were:

“There were so many progressive education elements in your lesson: constructivism, teacher as guide, taking students seriously, active engagement with materials, and it was concept-based (windows and mirrors).”

“The creation of the venn diagram, where people had to apply the concept of windows and mirrors to a brand new resource, was an excellent way to gather evidence of people’s understanding of the concept. I also like that you had people share this out loud to check for understanding (rather than turning in our written work, which would have been more difficult in a digital setting).”

“I appreciated how you facilitated people’s responses in the chat, and encouraged people to connect with one another via emojis and comments. Caitlin summarized what we put in the chat and pointed out the different ways people interpreted what we wrote–this is definitely a characteristic of “teacher as guide,” rather than ‘sage on the stage.’”

“You two killed it!!!! As I already shared, you designed a truly progressive education lesson that applied a constructivist pedagogy to deepen the group's understanding of the concept of "windows and mirrors." It was so incredible to see you start with what the group already knew, provide a definition, and then have the group unpack and dig deeper into the definition through activities like the venn diagram that integrated the diverse texts you selected. Finally you had us create something new with the concept! We ended with reflection–a hallmark of the pedagogy!”

Click on the links to view Dwayne and Keenan’s lesson plan about justice and Caitlin and Eugene’s lesson plan about “windows and mirrors.”

Big Takeaways, the Role of Lesson Planning in a Progressive Education

As a social studies methods professor, teaching pre-service secondary social studies educators how to design curriculum for their adolescent students, I always began my course with the students learning how to unit plan (using the Inquiry Design Model). I did this because I often observed brand-new teachers gravitating towards designing stand-alone, disjointed lessons that focused on discrete facts or skills, rather than engaging students in complete or holistic units of long-term study. This was a unique approach compared to other professors in the School of Teacher Education, who tended to start with teaching their pre-service teachers how to lesson plan, before they jumped into the seemingly more complex task of unit planning. I was of the opinion that if I started with unit planning, the pre-service teachers I worked with would understand that “lessons” should be designed to fit into larger learning segments–small interlocking parts of a whole–which could support students on their journey in constructing answers to the big questions, problems, and projects that frame our lives in this diverse democracy.

If I were asked to teach a social studies methods course again today, I would definitely stick to my progressive educator’s inclination to start with unit planning, teaching my students how to design Inquiry Design Model (IDM) Blueprints or PBL. However, when I got to teaching lesson plans, I think I would do a better job of engaging teacher candidates in applying core principles from a progressive philosophy and pedagogy to designing their lessons. This includes using a grounding question or concept to frame the lesson, ensuring that resources and experiences are culturally responsive and place-based, designing the learning so that students are constructing knowledge along the way, and making sure that the lesson has some elements of the criteria the Progressive Philosophy and Pedagogy students used last fall (see the list below).

Supports the development of the whole learner

Emphasizes community and collaboration

Meaningfully engages student interest and intrinsic motivation

Promotes inquiry and deep understanding

Utilizes direct experience and hands-on learning

Students (and teacher) reflect on experience to construct meaning

Includes interdisciplinary connections and applies to our lives outside of the classroom

Assessment values growth over time and is used for future goal setting

Promotes social justice and taking informed action

Incorporates wonder and play

Integrates the arts, multiple intelligences, and/or other interdisciplinary connections

It seems simple, but I think it is important to emphasize that the same defining features used to design progressive education schools, programs, curriculum and units of study should be applied to progressive education lesson planning.

With that said, curriculum design–whether it is units or lessons–is only one part of the equation when delivering a high-quality progressive education. This sentiment is echoed by Kilpatrick, who “expressed several warnings in an adoption of a project method approach. He voiced a need for changes in textbooks, [or other curricular materials], grading, and student advancement as well as modifications to furniture and school architecture. Most insightfully, he…recogniz[ed] the need to adequately educate teachers” (Pecore, 2015, p. 167). And part of this education includes the reminder that progressive education teaching is both a science and an art–and part of the art is being able to respond to students in the moment and adjust the plan accordingly. This ability to make on-the-spot decisions and creatively meet the “teachable moment” with grace, fluency and ease is a hallmark of a progressive educator and just as critical as learning how to design solid progressive education curriculum, unit and lesson plans alike.

Works Cited:

Kohn, A. (2015). Progressive Education: Why it's Hard to Beat, But Also Hard to Find. Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/progressive/2

Markham, T., Larmer, J., & Ravitz, J. (2003). Project based learning handbook: A guide to standards-focused project based learning for middle and high school teachers. Novato: CA: Buck Institute for Education.

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Pearson. Copy citation. Chicago style citation.

ABOUT THE Contributors:

Dr. Amber Strong ’89 Makaiau is a Specialist at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Director of Curriculum and Research at the Uehiro Academy for Philosophy and Ethics in Education, Director of the Hanahau‘oli School Professional Development Center, and Co-Director of the Progressive Philosophy and Pedagogy MEd Interdisciplinary Education, Curriculum Studies program. A former Hawai‘i State Department of Education high school social studies teacher, her work in education is focused around promoting a more just and equitable democracy for today’s children. Dr. Makaiau lives in Honolulu where she enjoys spending time in the ocean with her husband and two children.