By Gabrielle Ahuliʻi Ferreira Holt

There is incumbent upon the teacher who links education and actual experience together a more serious and a harder business. He must be aware of the potentialities for leading students into new fields which belong to experiences already had, and must use this knowledge as his criterion for selection and arrangement of the conditions that influence their present experience (p. 33).

-John Dewey, Experience and Education (1938)

As we continually explore the question of what it means to be a progressive educator, one of the answers we consistently return to is the idea that progressive education instills within the child a lifelong love of learning. John Dewey made this clear (and a central part of his text Experience and Education) when he wrote, “The most important attitude that can be formed is that of the desire to go on learning” (p. 20). In progressive spaces, we ensure this in many ways - by facilitating hands-on, student-guided learning; by following children's lead in the classroom, and, as Julie Stern writes in her text Conceptual Understanding: Harnessing Natural Curiosity for Learning that Transfers, by “respect[ing] the developmental stages of childhood with intellectual rigor” (p. 4).

One of the most effective ways an educator can do this is through the use of a concept-based curriculum - using concepts to frame the topics of study and ensure the creation of enduring understandings that children form through crafting connections across subjects. In this article, I’ll define what concept-based learning is, provide further connections to the principles of progressive education, demonstrate what it looks like in practice, and, hopefully, make it easier for other educators to adopt this type of teaching and learning in their own classrooms.

Throughout this piece, I will use the topic of Hawaiian History to illustrate examples of concept-based curriculum design and instruction in action. My hope is that by using a topic that is a requirement in the Hawai‘i State Department of Education social studies curriculum, it will help teachers to understand how they might adopt this type of teaching and learning easily. One of the biggest misconceptions about concept-based instruction is that it is not possible to facilitate when your program is “constrained” by required core standards. This is not the case. Teachers who have a tried and true curriculum can apply a conceptual lens to their units to allow students to have a deeper understanding of the content, and provide them an elegant leaping off point into further units of study.

An important note: like progressive education (see this previous blog), concept-based learning is not a dichotomy - it is a spectrum. Take the tools that you can apply, use it where and when you can, and adjust when you need to.

Defining Concept-Based Learning

Conceptual frameworks can be used by educators to help children make connections when learning. By definition, a concept is an abstract organizing idea that helps us categorize facts and make connections between different topics. Concepts make excellent starting points for designing meaningful learning experiences for students. They are abstract, universal, timeless and broad, while topics are specific, content-based, and concrete. As H. Lynn Erickson explains, “[Concepts] serve as the bridge between topics and generalizations” (p. 28). Because these concepts are abstract and universal, every student can approach a brand-new topic of study through their own lived experiences - an essential principle of progressive education, and a way to ensure that each child feels they have something to contribute to the work.

At Hanahau‘oli School, the eight-year program is primarily guided by concepts - we see concepts guiding units of study across grade levels which help create a broad, thematic continuity in the eight-year journey of the Hanahau‘oli student. Some concepts that are used throughout the program are:

Belonging

Change/Constancy

Basic Needs

Diversity/Unity

Self/Society

Interdependence

Survival/Adaptation

Freedom/Power

Reciprocity/Responsibility

We see these concepts serve as guides to all manner of topics at Hanahauʻoli - “Insects”, “Shelters”, “The Water Cycle”, “Biodiversity in the Hawaiian Islands”, “The Contemporary Islamic World”, etc. A conceptual lens helps to organize your unit of study and allow your students to see connections between all of their learning - even outside the classroom you share.

Topics like The History of Enslaved Peoples and Contemporary Hawaiian History will not seem topically related in a student’s mind, but when examined through the lens of Self/Society or Power/Freedom, a child may begin to explore and interrogate the conceptual connection between those topics. They may begin to ask questions based on a conceptual understanding, and as an educator, you may begin to pose these questions to them - questions like, “How has freedom been defined historically, and how has the definition changed over time?” or “What is the impact that people in power have on a societal understanding of freedom?” Students can answer these conceptual questions using evidence from all of their units of study, not just the one they are currently engaged with.

The conceptual questions help to increase engagement with these topics, as they often offer a more relevant lens to what may seem distant and disparate ideas.

It also encourages understanding beyond topics and facts - in Erickson’s text, she shares a diagram on page 31 of a structure of knowledge and what that looks like in the conceptual classroom:

(P.31, 2008)

You can see from the diagram that by focusing just on the skills and facts, a student will not be able to progress beyond the first level of knowledge.

In order to create true understanding and complex theory making, teachers must provide students with a scaffolded series of learning experiences that build their conceptual understanding. This is not to say that the first level of this structure is without value - John Hattie goes on to explain that there are three levels of learning: Surface, Deep and Transfer. He explains, “Together, surface and deep understanding lead to the student development of conceptual understanding.” (p. 61). Keeping this in mind, we see that facts/knowledge is the first step in a child’s learning, which, in the conceptual classroom, works alongside deep conceptual learning to create true, meaningful understanding.

H. Lynn Erickson is one of the, if not the, foremost writer and scholar in the field of concept-based education. In her work Stirring the Head, Heart, and Soul: Redefining Curriculum, Instruction and Concept-Based Learning, she writes, “...studying topics and facts as knowledge to be memorized fails to engage the deeper intellect of students. When students are encouraged to think beyond the facts and connect factual knowledge to ideas of conceptual significance, they find relevance and personal meaning” (p. 24). By encouraging students to build synthesis between their factual knowledge and conceptual understanding, we are thinking beyond.

Much of this work is also based on the work of Hilda Taba, a teacher and educator who was exploring this work in the 1950s and 1960s. In her published study Teaching Strategies and Cognitive Functioning in Elementary School Childrenshe writes:

The chief hypothesis of the study was that if the students were given a curriculum designed to develop their cognitive potential and theoretical insights, and if they were taught by strategies specifically addressed to helping them master crucial cognitive skills, then they would master the more sophisticated forms of symbolic thought earlier and more systematically than could be expected if this development had been left to the accidents of experience or if their school experience had been guided by less appropriate teaching strategies. The assumption was that conscious attention to the various intellectual processes would be the chief factor that would affect the students' facility to transform raw data into usable concepts, generalizations, hypotheses, and theories…Generally speaking, the results of this study confirmed these hypotheses (1966, p. 233).

In summary, teachers have the potential to support students through the process of developing deep and sophisticated conceptual understandings of themselves of the world around them if they adopt a particular approach to curriculum design. This is now called concept-based teaching and learning.

Choosing the Conceptual Lens

The first step in crafting a concept-based thematic unit of study is composing the conceptual lens. Most educators will already have this foundation set in place - either through the scaffolds provided by content standards, (an example being Content Standard SS.7HHK.2.17.2: “Assess the social and cultural changes resulting from missionary influence in Hawaiian society”) or by virtue of having taught a particular topic before and knowing the larger concepts connected to a particular topic. For example, English Language Arts teachers know that the novel To Kill a Mockingbird can be helpful in teaching concepts like prejudice, social injustice, and courage. It is also important that teachers consider whether particular concepts meet the developmental needs of their students.

Using the (above) structure of knowledge diagram might be a helpful planning tool - starting at the bottom, ask yourself, “what is essential for children to know about this topic?” Once these are established, you may begin to brainstorm the conceptual framework around your topic. Choosing this concept might be tricky - however, as Julie Stern (2018) states, “The concepts should be inherent in the content of your course and the ways of thinking that are important in your field” (p. 27). It may also be helpful to start at the top of the structure - what testable theory would you imagine your students might form, after having gone through this unit of study? The conceptual lens is often given in pairs - “Self/Society”, “Conflict/Harmony”, “Survival/Adaptation”, etc. They may also be broad, singular terms - “Interdependence”, “Cycles”, “Choice”, etc.

As an example, I will again return to the topic of Contemporary Hawaiian History (1793 - 1893). If we were to explore this topic, students would primarily learn just the facts of this era - facts pertaining to the chiefs, events in Hawaiian history, etc. By sticking to just the first level of the Knowledge Structure, children would indeed learn about this time, but would not be given the tools or opportunity to dig deeper and form theories about how the world works. It would also fail to explore the very real and complex issues that the Hawaiian Kingdom faced during this era - because the conceptual lens would encourage the formation of theories, students will get a much more nuanced understanding of this time. This type of fact-based learning fails to be transferable - the knowledge they would acquire about Hawaiian history only apply in this one, specific unit of study. On the other hand, if students were able to study contemporary Hawaiian history using a conceptual framework–grounded in concepts like colonization, cultural transformation, and governance—students would more likely transfer or make connections between what they are learning in Hawaiian history to other content areas and topics.

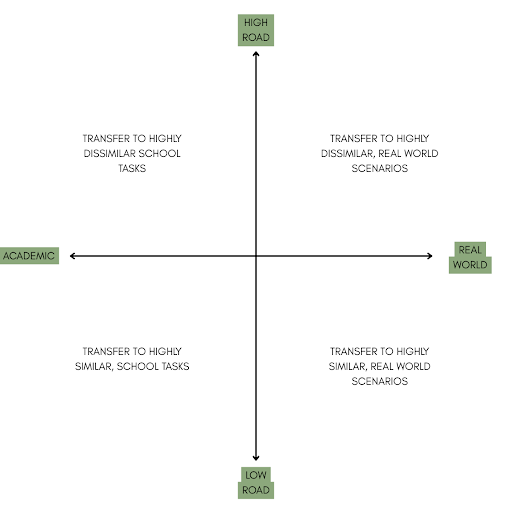

Transferable learning means that the student goes beyond making connections in their learning (“this reminds me of _____”) - as Julie Stern explains, “Conceptual transfer only occurs when students apply insights about the relationship among concepts to a new scenario” (p. 32). We are also looking for “high-road transfer” (p. 32) - where learning innovation happens, and where students apply their learning to dissimilar, real-world situations.

Stern, Ferrano & Mohnkern (2016)

Another interesting facet of concept-based instruction is that there are many ways to explore the same topic. As an example, examine how I apply both the conceptual lens of Control & Communication and Power & Freedom to the topic. You will see how these conceptual lenses subtly shift the way students explore the topic (and may also change the specific sub-topics) but still grapple with much of the same content and core ideas.

If we apply what students have learned in these concept-based explorations to the structure of knowledge, it may look like so:

Through these concepts, students will reach transferable understanding - they can test the theory they come to over and over again in every unit of study.

For example a student who can craft the above theory (“Rapidly evolving technologies are a lever of change in society”) may transfer this learning to a future study of US democracy. As they explore how evolving technologies had an effect on the emerging economy of the 19th century United States, they may see how the generalization they developed in their study of Hawaiian history can also be applied to US history. In a high road transfer, students might begin to apply their theory in a study of contemporary US democracy - asking critical questions of the roles that AI, social media and wider “internet culture” might play in the formation of active citizens. They may also encounter cases in their learning where the theory they formed is not true; therefore, the student becomes a scientist, proving and disproving their theories over and over again.

Crafting Meaningful Essential Questions

Another critical component of designing concept-based curriculum is the process that teachers must go through to generate an “essential” question that can be used to frame a unit of study. In my experience, not all driving/essential questions are created equal and some help to shape a unit of study better than others. Essential questions are instrumental in helping students to understand that their learning is a part of problem-solving; we are posing these questions to them so that they may begin to tackle large-scale problems of the world.

In their text Concept-Based Inquiry in Action: Strategies to Promote Transferable Understanding, Carla Marschall and Rachel French state, “Guiding questions scaffold student thinking toward the generalizations [in a conceptual classroom, learning outcomes are often referred to as generalizations]. There are three types of questions that we construct: factual, conceptual and debatable” (p. 47).

They define the three as follows:

Factual - “These questions address unit content, highlighting factual examples…They focus our topic and support student comprehension of critical knowledge” (p. 50). These types of questions are “locked into” the subject - they are not broad or abstract. Factual questions are an important building block of understanding. Using the example of Hawaiian History, factual guiding questions might look like:

How was the Hawaiian language adapted into a written language?

When and how did the Māhele happen?

How was the kingdom of Hawai‘i created?

When were the diseases of smallpox and Hansen’s disease introduced to Hawai‘i?

Conceptual - These types of questions are “open enough to allow for a range of student responses, but also structured in a way to guide teaching and learning” (p. 50). Crafting these questions in the present tense will help ease transfer:

What impact do public health crises have on communities?

How does communication change in a crisis?

How do human beings express themselves and their culture?

What is the connection between literacy and national identity?

Debatable - Also called “provocative questions”, these questions help to invite discourse. They help to facilitate strong, persuasive, evidence-based thinking and writing. “They can be factual or conceptual, but are written to have no ‘correct’ answer…provocative questions support students in applying their knowledge, and are thus extremely useful in encouraging students to apply their understanding” (p. 51). Some debatable questions raised in a study of Hawaiian History might look like:

Does culture change and adapt over time? How might cultural change affect members of that cultural group?

How did the medical incarceration of Hansen’s disease patients affect the Hawaiian Kingdom?

What role did literacy play in the formation of the modern Hawaiian nation?

When put together, your guiding questions should address all levels of the Structure of Knowledge. New questions might also emerge as you move through this unit - do not be afraid to integrate them into your work as you go.

As a final statement on questions, I want to examine a given essential question - “Was unification good for the Hawaiian kingdom?” At first glance, this may seem like a good example of a debatable question - however, it is a weak question because of the way it is written. There is no real relationship stated in this question; the verbs are inactive and, most importantly, the answer that a student might come to would not be transferable. It would only apply to this specific topic. To rewrite this question with a conceptual lens, we might ask:

What is the consequence of Hawaiian unification on the Hawaiian identity?

Did unification create a stronger kingdom?

How did Hawaiian leaders balance perpetuation of a kingdom and its people amid rapid change?

When stuck, try to craft questions in a way that states a relationship, and uses active verbs and descriptive vocabulary. “How does ____impact _____”; “How do _______ and _____ interact?”; “What is the relationship between _____ and _____?” are all great ways to start. These types of questions work because they force investigation into the relationships between your given topic and the broader, conceptual generalizations that your students will be generating.

Composing Sophisticated Learning Outcomes

H. Lynn Erickson (2008) talks about generalizations or learning outcomes as “enduring understandings”. On page 87, she explains, “generalizations are statements of a conceptual relationship…they transfer through time and space and across cultures and situations. They are exemplified through the fact base but transcend single examples” (p. 87). Like Marschall and French, she recommends crafting them using the present tense. They must also answer the guiding questions you have created for your unit of study. It is also important to remember that a generalization is not a fact. Your generalizations are ensuring that your students are reaching transferable yet deep understandings. A statement that contains two or more concepts is ideal.

In Julie Stern’s book, she provides some helpful guidelines. One of the most helpful assertions she makes is that the generalization “needs to be significant. If it feels really obvious or simple, it’s not done, unless it is something that students often misunderstand or struggle to grasp”(p. 27).

Let’s use the example learning outcome “Students will learn about the lives and reign of the aliʻi of the Kamehameha period.” While fact-based, we can rewrite this generalization in a way that still encourages factual learning while digging deeper. This is a weaker generalization because there is no conceptual relationship stated, and, by just focusing on this, there will be no transferable learning acquired.

Rewriting this learning outcome into a generalization might look like, “Students will understand the impact that introduced diseases, political conflict and religion had on the aliʻi of the Kamehameha period.” This is a stronger generalization because there is a relationship stated, with a strong verb like “impact” integrated into it. There will also be transferable understanding - having lived through a pandemic, many of our current students may be able to draw a conclusion about that era of world history and how it relates (or not) to more contemporary public health crises.

Last Thoughts & Reflections as an Educator

When conceptual learning happens in the classroom, you will see students’ reflections and discussions become more profound, as they begin to have epiphanies about how the world works and their place in it. You may also begin to see connections being made that even you as the educator didn’t establish!

Below is a picture of a class brainstorm my 4th & 5th grade students did at the end of their 2020 - 2021 school year. As part of one of the last learning experiences of the year, I wanted to provide them with the opportunity to learn how to craft a strong thesis statement, writing their theory developed over the course of the school year and supporting it with evidence from all of their learning experiences over the course of the school year.

This documentation of their group discussion is a clear demonstration that when the learning is tied by concepts, children make deep, meaningful connections in their content:

You can see how disparate topics such as Nazi-occupied Denmark, medical incarceration in Hawai‘i and the American civil rights movement become deeply connected in children' s minds through the broad concept of freedom, and the posing of a debatable question as the one above. You can also see that children made connections to their real-world experiences - to current events of the time and to a guest speaker at their assembly. This is perhaps one of the most valuable lessons I learned as a teacher - that what we do in the classroom truly helps prepare them not just for future learning, but for understanding their world.

One of the key benefits of this type of deep, meaningful connection-making is the formation of theories and generalizations about the world. When students are given opportunities to posit theories, they are beginning to become active participants in their own society. As progressive educators, we know this to be a guiding principle - that we are preparing children for participation in a diverse democracy.

I will also go one step further - by encouraging this type of learning, particularly in Hawaiʻi for Kanaka ʻŌiwi children, we are cultivating an environment in which we empower them to participate in civic discourse, a right (and responsibility) handed down to us from our kūpuna. H.Lynn Erickson (2008) makes this plain: “Global interdependence and sophisticated technologies require that we raise the intellectual as well as the content standards in classrooms” (33). Active participation in civic discourse is a natural consequence of this type of learning - students who are given the opportunity in their classrooms to reach high-road transfer will naturally begin to apply their learning in those real-world scenarios that democratic participants encounter day after day. Echoing Dewey’s assertion about “the most important attitude”, Erickson concludes that “Children who love to learn do so with their minds, hearts and souls…Loving to learn is a gift…Creating a love of learning means discovering a wellspring of talent, supporting the flow of energy, and celebrating success along the way” (230).

If there is any higher calling in this world, it escapes me now. As progressive educators, we can do the best for all of our students by capturing their minds, hearts and souls in order to craft a better future society for all.

Works Cited:

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. Touchstone.

H Lynn Erickson. (2008). Stirring the head, heart, and soul : redefining curriculum, instruction, and concept-based learning. Corwin Press.

Hawkins, D. (1965, February). Messing About In Science [Review of Messing About In Science]. National Science Teachers Association.

Marschall, C., & French, R. (2018). Concept-based inquiry in action : strategies to promote transferable understanding. Corwin, A Sage Company.

Stern, J., Lauriault, N., & Ferraro, K. (2018). Tools for Teaching Conceptual Understanding: Harnessing Natural Curiosity for Learning that Transfers. Corwin.

Taba, H. (1966). Teaching Strategies and Cognitive Functioning in Elementary School Children.

Zupančič, M. (2022). John Hattie, Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey, Visible Learning for Mathematics: Grades K-12: What Works Best to Optimize Student Learning, Corwin Mathematics: 2017; 269 pp.: ISBN: 9781506362946. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 12(1), 241–246. https://doi.org/10.26529/cepsj.1419

Further Reading (Books not cited but highly recommended to support this work):

H. Lynn Erickson, & Lanning, L. A. (2013). Transitioning to Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction. Corwin Press.

Erickson, H. L., Lanning, L. A., & French, R. (2017). Concept-based curriculum and instruction for the thinking classroom. Corwin, A Sage Publishing Company.

Mustafa Yunus Eryaman, & Bruce, B. C. (2015). International Handbook of Progressive Education. Peter Lang Gmbh, Internationaler Verlag Der Wissenschaften.

Posner, G. (2003). Analyzing the Curriculum (3rd. ed.) McGraw-Hill Education.

ABOUT THE Contributor:

ʻO Gabrielle Ahuliʻi Ferreira Holt ke kahu puke ma ke kula o Hanahauʻoli, ma Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. He MLIS kona mai ke kulanui o Hawaiʻi ma Mānoa, a he BFA kona mai ke kulanui o British Columbia (ma ka ʻāina ʻōiwi no na poʻe xwməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), Stó:lō and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil- Waututh).

Gabrielle Ahuliʻi Ferreira Holt is the librarian at Hanahauʻoli School in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. She has a MLIS from the University of Hawaiʻi and a BFA from the University of British Columbia (situated on the unceded territories of the xwməθkwəy̓əm [Musqueam], Skwxwú7mesh [Squamish], Stó:lō and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh [Tsleil- Waututh] nations.) She is a third-generation graduate of Hanahauʻoli.