Image generated by Gemini 3 Flash (Google) based on user prompts

The constant onslaught of new innovations within Artificial Intelligence (AI)–specifically Generative AI (GenAI)–and the expansive impact AI has had on the workforce and economy can feel overwhelming. Everything and everyone appears to be rushing towards AI (Giattino et al., 2023), for the same reason Jeff Bezos ran to the field of digital commerce (Locke, 2020), and now, our economy reflects and has become dependent on AI’s growth (Sigalos, 2025). Naturally, education has followed this influx towards AI with individuals and institutions racing to be on the front end of the innovation adoption curve (“Rogers’ Innovation Adoption Curve,” n.d.), either for the benefit of human development, building capital, or both. From my perspective, this is not a fad. Education is an ecosystem mostly bound by time constraints of a school year, school day, class periods, etc... And in time-bound ecosystems, speed wins. Just like with any technological innovation, AI makes processes or products happen faster, which is of value in a capitalist economy. As a result, I believe we are in the midst of our next evolution in education with the rise of AI. To borrow from the metaphor of surfing–educational stakeholders can either miss it, get crushed by it, or paddle, catch, and safely ride the wave. In fact, we might even find ways to face our fears head on and enjoy riding the waves of this upcoming swell of educational evolution driven by technological innovation.

To be clear, I am not a surfer, though I wish I was. Surfing is a dangerous sport which requires expertise to navigate safely. Even with their advanced swimming ability, surfers don’t just paddle out on any set of waves. Experts know the surf spots, where the channel is, when good sets are coming in, the etiquette for sharing the waters with other surfers, and how to safely negotiate their way around other surfers with wide ranges of abilities. They have the knowledge and skills to ride the wave.

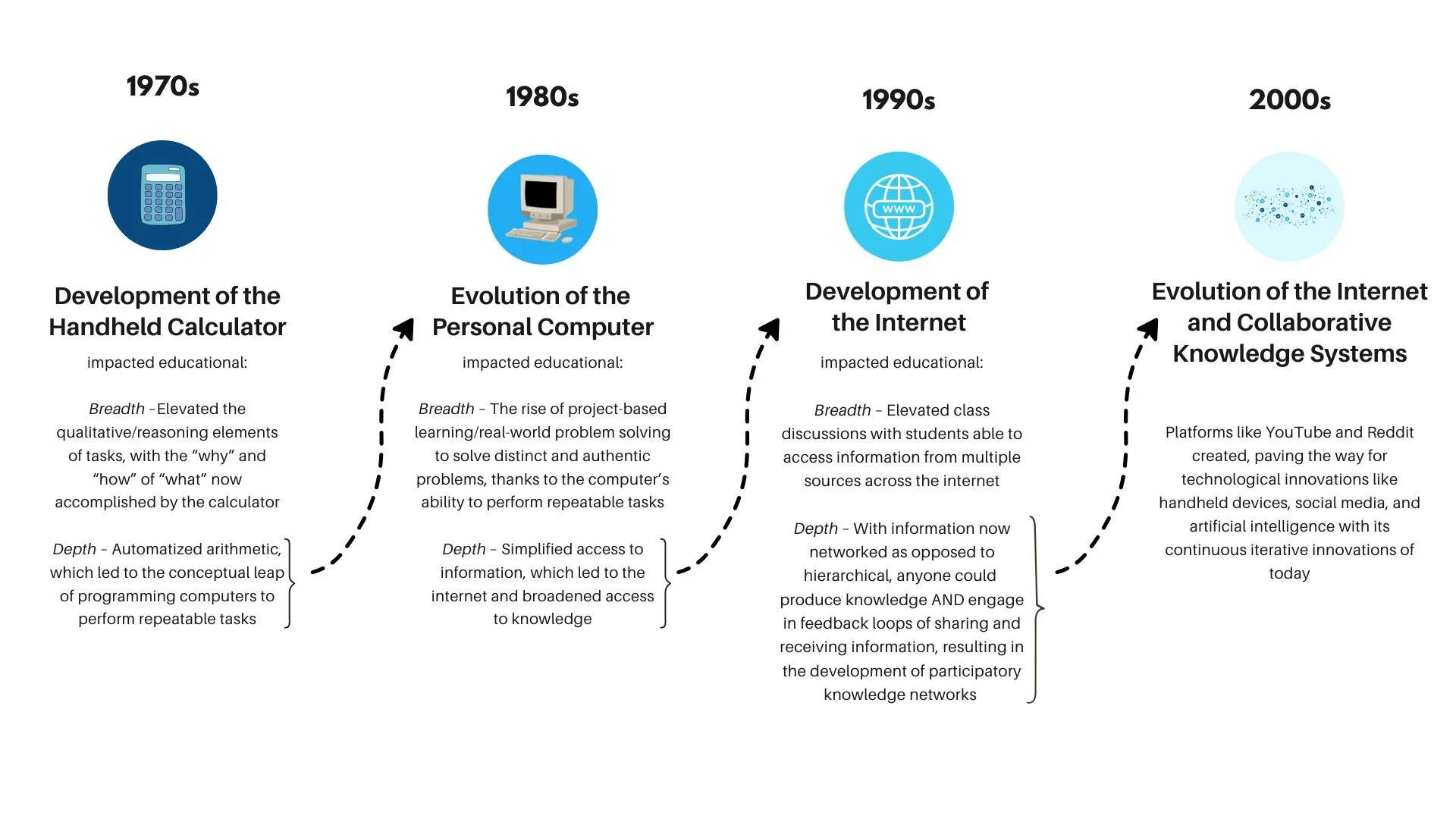

Therefore, I believe the first step for educational stakeholders in this particular moment is the need to develop the skills and knowledge necessary for riding this next wave of educational evolution–driven by AI. I write “next wave” because the impact of technological innovation on education is not a new phenomenon. We have had similar waves in the past. And if we were to critically analyze educational evolutions of the past, we would see the cyclical nature of each educational evolution. Each of them starts with a technological innovation that catalyzes change in the environment, forcing “breadth and depth” plasticity upon stakeholders, the depth of which creates the next technological innovation, and then the cycle repeats.

As a reference, this historical timeline is helpful:

For those wondering “what’s next?”, the answer is autonomous systems and quantum computing. The point here is, this wave of educational evolution with AI, like any other technological innovation, is predictable.

Understanding the predictability of waves of educational evolution comes with the burden of knowing that each evolution has had its share of crashes [negatively affecting learners] in response to technological innovation. The pessimist in me already looks at how AI will displace critical reasoning the same way GPS and smartphones have displaced spatial memory (T. Gammarino, personal communication, March 29, 2023), partial navigation, and mental mapping (Gonzalez-Franco, Clemenson, & Miller, 2021), or how calculators have impacted mathematical abilities (Wan, 2024). Negative effects of AI use were already observed from a study conducted by MIT, which provided preliminary data on pitfalls with AI–that there is “likely decrease in learning skills” (Kosmyna et al., 2025, p. 2) when an LLM (Gen AI large language model) is used to help write papers. Kosmyna et al. shared that a group that used LLMs at the onset of a task “outsourced cognitive processing to the LLM” (p. 140) or metaphorically used the AI as an external hard drive instead of internalizing the learning in their own brain for memory. This suggests that the use of AI, particularly to initiate a task, may be detrimental to learning and cognition.

To balance my pessimism, the optimist in me is excited for the learning we can provide with AI, and how we can prepare to move forward to the betterment of education as a whole. I was interested to learn that in the MIT study, metacognition and retention of knowledge was greater in the “Brain-to-LLM” (Kosmyna et al., 2025, p. 140). This suggests that learning may be enhanced when a user independently ideates and grapples with such ideation, and then iterates with support of the LLM. Kind of like the “think-pair-share” instructional strategy. This approach of independently working on a task before being brought to a group for collaboration is an effective strategy supported by the research of Hattie, Fisher, and Frey (2017). More importantly, we have enough historical data from past educational evolutions–and early data from AI use–to strategize an approach moving forward with AI and any further evolutions in education.

As I take all of this into consideration, I would like to propose a framework, which can help educators to take a more conceptual approach to the upcoming educational evolution that has already begun–a framework that can support them as they respond to the technological innovations of our current moment. The framework to follow starts with improv’s “yes, and” approach. Educators must first identify, and then:

Preserve the human cognitive skills that are threatened to be displaced through use of the technology.

Develop the skill(s) that will ethically optimize use of the technology.

Create curricular engagements for increasingly contextualized learning.

Cultivates authentic human-to-human connection.

To illustrate this framework in action, the examples below demonstrate how each step of this framework can be applied to thinking about the impact of AI on teaching and learning and how educators might adjust their practice.

1. Preserve the human cognitive skills that are threatened to be displaced through use of the technology.

From a user-generated prompt, GenAI can synthesize information and create personalized output. The three skills threatened to be displaced are critical thinking, creativity, and communication. We must preserve these skills through intentional curriculum, instruction, and assessment. If we don’t, then we will decrease our own ability to (a) synthesize authentic information we receive, and (b) create engaging content for others. Cognition will deteriorate, information will be homogenized, and new knowledge may cease to exist. Let me explain. By having AI synthesize information, we will be less tolerant of any information unsynthesized by AI. Extraneous information, outliers, or unorganized data will make us uncomfortable and be seen as inconvenient. We will increasingly seek and prefer homogeneity for comfort.

With information attainable on-demand, our brains outsource retention of knowledge to technology and retrieval to AI. Additionally, to make the predictability of homogeneous output engaging, we’ll use GenAI to bring excitement by personalizing the output. This personalized output renders any non-personalized delivery as “uninteresting.”

Here is the research to back this up: In a study examining GenAI’s (generative artificial intelligence) capabilities to achieve creative scientific discovery, Ding (2025) shared that GenAI was “not yet able to autonomously make original scientific discoveries with either an unknown conceptual space or a task that requires venturing beyond the domain knowledge space of human scientists” (p.10). In a similar study utilizing puzzles conducted by Apple © , Shojaee et al. (2025) shared that “despite sophisticated self-reflection mechanisms, these models fail to develop generalizable reasoning capabilities beyond certain complexity thresholds” (p. 11). LLMs cannot create new or novel ideas. Instead, Bender (2025) writes, “what large language models are designed to do is to mimic the way that people use language. Based on very large input datasets, they can output text that takes the form of a medical diagnosis, a scientific paper, or a tutoring session. But the key thing to know here is that these models only ever have access to form: the spelling or sometimes the sounds of words” (p. 41). LLMs produce the illusion of thought, the illusion of ideation, a “trick” (Bender, 2025, p. 41) with limitations based on the data set the LLMs have been fed. The act of generating one's own thoughts and ideas has benefits beyond learning, to preserving human-centered abilities for creating new knowledge and solving complex problems.

To summarize, the individuals that rely on AI too heavily will be inflexible, unresponsive, intolerant, and incapable of creating new knowledge. This may get to the point where AI will be required as a mediator between humans, or act as a CEO for decision-making. We must use AI in an ethical manner that preserves human cognitive skills. It starts with knowing how AI (and any technology) should be used.

2. Develop the skill(s) that will ethically optimize use of the technology.

How can we use technology ethically without hindering human cognition? One answer might be to help us reduce redundancy.

For example, the calculator’s intended use was to do arithmetic that we already knew how to do, but faster. Also, the internet gave us faster access to information than to our use of a physical library. In addition to the previously stated potential learning benefits with AI, we can use GenAI for repeatable written tasks.

Here are the applications to the present: People who are using LLMs to repeat minor variations of written work “in their tone” are spending less time creating the written work (M. Proctor, personal communication, September 25, 2025), and more time (a) prompt engineering and (b) editing the LLM’s production. To do this, individuals provide their own writing samples to fine-tune the LLM, and then provide the prompt for the LLM to generate. In order to do this well, the individual will know how to select useful written work for fine-tuning, then write a clear and meticulously explicit prompt with the goals of requiring the least amount of iterations for revision. Again, those doing this well will anticipate the LLM’s response and be prepared for revisions, or even prevent revisions by having it proactively addressed in the prompt. When editing the LLM’s generated writing, the individual must consider the message, make sure it does not sound like AI, and ensure all necessary details are in the written piece. They will have the “eye of precision”, able to swiftly and precisely comb through written pieces, and make appropriate adjustments before publishing it.

There are immense amounts of cognitive and technical skills required in the task above. Cognitively, the user must be able to identify useful prior written samples for fine-tuning, anticipate what the LLM will produce, evaluate the production, and reflect and ideate next steps for revision. From a technical lens, the user must know how to write the appropriate prompt and revise prompts for prompt conditioning.

All of these skills could be intentionally developed through curriculum instruction, and assessment, in isolation or integration. A simple task can be for students to find useful text to help fine-tune a model. Or you can share everything provided by a prompt, and anticipate what the model will produce. In mathematics, students can be provided with an incorrectly completed problem for students to revise.

These skills can also be developed through values and mindsets.

For example, “kilo” is the Hawaiian word that represents the value of skilled observation. It goes deeper than that, as it is valued for its ability to produce attentiveness and mindfulness. By intentionally practicing kilo, one’s observation skills are heightened to be able to notice distinct, meticulous elements.

Additionally, from a mindset perspective, humans are epistemically attuned to potential threats and allocate greater cognitive resources to evaluate potential dangers than neutral stimuli. By shifting the mindset from “is there a revision to make?” to “what part is negatively affecting the rest of the work?”, the individual is more likely to find and address elements of their work.

The possibilities are endless. Regardless, we need to develop these skills (and whichever future skills that emerge) to ethically optimize proficient use of GenAI.

3. Create curricular engagements for increasingly contextualized learning.

The question teachers should always be asking is how do I contextualize a lesson into a [learning] experience? Lessons can be delivered and learned from anyone, by anyone, to anyone, anywhere. By contextualizing lessons, learning is unique to the people, time, and place. An experience engages all of those elements. Yes, lessons have the capability of transferring knowledge, though experiences can create core memories.

AI can deliver personalized lessons, though the context is either digital or synthetic. Increasingly contextualized learning converges learning to be authentically localized to an unreplicable experience. As we recall, GenAI has the ability to replicate and teach lessons that are replicable. By contextualizing learning to the context of people, time, and place, we create a curricular engagement that cannot be repeated. It is an experience worth experiencing for teachers and students who are all learning in the space.

While many curriculum tasks are not contextualized to place, we can ensure instruction cultivates contextualized learning from the people involved through their insights serving as elements of the curriculum. This contextualizes the learning to the people involved, and fosters empathy for diverse thought, reducing the potential for homogeneity. The art of contextualization will need to be mastered by future educators.

4. Cultivate authentic human-to-human connection.

We've learned from the COVID-19 pandemic that interpersonal in-person engagement in work and at school is not grounded in our desire for collaboration, but for connection. As a result, we’ve allocated resources to create the space to do so. In education, the market for Social Emotional Learning (SEL) has risen (G. Likhil, 2022), and in business and industry, we know of the “fun” tech campuses provided by Google and Meta, and are even seeing banks like Chase creating new buildings with amenities (JPMorgan Chase & Co., 2025) to inspire in-person engagement.

We are well aware of the dangers of AI and its ability to simulate an artificial connection with the user. How do we ensure that students don’t form such a connection with AI? Start by creating the conditions for the alternative.

Protect the physical, social, and emotional safety required for interpersonal engagements.

Provide activities and tasks that promote collective understanding over task completion.

Encourage inclusiveness and curiosity as a means to broaden one’s own understanding.

Equip students with prompts that extend thinking through questions. Questions keep the conversation, and learning, going. With answers, everything stops.

Students don’t want to connect with technology. Technology is their outlet from their discomfort of the in-person experience. By creating a safe environment, worthwhile interpersonal in-person engagements (and the conditions to successfully engage within them), we can foster human-centered connection.

In summary, AI is not going away. It's yet another technological innovation forcing the next wave of educational evolution. Let's not let it crash us, but instead, let's get stoked on preserving the human cognitive skills AI threatens to displace, develop the skills for ethically optimizing use of the technology, create increasingly contextualized learning, and cultivate authentic human-centered connections. Let's build the knowledge and skills to ride this wave and the next one. It’s going to be gnarly, but it might also be fun and enlightening in unexpected ways.

References:

Bender, E. M. (2025). We do not have to accept AI (much less GenAI) as inevitable in education. In AI and the future of education: Disruptions, dilemmas and directions (pp. 41–45). UNESCO Publishing. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000395236

Ding, A. W., & Li, S. (2025). Generative AI lacks the human creativity to achieve scientific discovery from scratch. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 9587. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93794-9

G. Likhil. (2022, January). Social and emotional learning (SEL) market: Forecast & demand 2030. Polaris Market Research. https://www.polarismarketresearch.com/industry-analysis/social-and-emotional-learning-sel-market

Giattino, C., Mathieu, E., Samborska, V., & Roser, M. (2023). Artificial intelligence. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/artificial-intelligence

Gonzalez-Franco, M., Clemenson, G. D., & Miller, A. (2021, May 7). How GPS weakens memory—and what we can do about it. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-gps-weakens-memory-mdash-and-what-we-can-do-about-it/

Google. (2026). Gemini (3 Flash version) [Generative AI]. https://gemini.google.com/

Hattie, J., Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2017). Visible learning for mathematics: Grades K–12: What works best to optimize student learning. Corwin Mathematics. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/visible-learning-for-mathematics-grades-k-12/book255006

JPMorgan Chase & Co. (2025, October 21). JPMorganChase celebrates grand opening of new global headquarters at 270 Park Avenue. JPMorgan Chase. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/newsroom/stories/jpmc-celebrates-new-global-hq-at-270-park-ave

Kosmyna, N., Hauptmann, E., Yuan, Y. T., Situ, J., Liao, X.-H., Beresnitzky, A. V., Braunstein, I., & Maes, P. (2025). Your brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of cognitive debt when using an AI assistant for essay writing task. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.08872

Locke, T. (2020, January 17). At age 30, Jeff Bezos thought this would be his one big regret in life. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/01/17/at-age-30-jeff-bezos-thought-this-would-be-his-one-big-regret-in-life.html

Rogers’ Innovation Adoption Curve [Figure]. (n.d.). ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Rogers-Innovation-Adoption-Curve_fig1_370863661 (Note: Content originally appears in The Economics of Exclusion: Why Inclusion Doesn’t Fit Fashion’s Business Model, which discusses Rogers’ curve).

Shojaee, P., Mirzadeh, I., Alizadeh, K., Horton, M., Bengio, S., & Farajtabar, M. (2025). The illusion of thinking: Understanding the strengths and limitations of reasoning models via the lens of problem complexity [PDF]. Apple Machine Learning Research. https://ml-site.cdn-apple.com/papers/the-illusion-of-thinking.pdf

Sigalos, M. (2025, October 22). Your portfolio may be more tech-heavy than you think. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2025/10/22/your-portfolio-may-be-more-tech-heavy-than-you-think.html

Wan, H. (2024, March 12). Over-reliance on calculators: A heavy burden on fundamental education. Ivy League Education Center. https://ivyleaguecenter.org/2024/03/12/over-reliance-on-calculators-a-heavy-burden-on-fundamental-education/

ABOUT THE contributOR:

Joseph Manfre is a 7th grade mathematics teacher at Punahou School and Ph.D. student in Education - Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Originally from New York, he earned his B.A. in Mathematics from CUNY Queens College before moving to Hawai’i in 2012. He has served as a classroom teacher, instructional coach, and State Mathematics Educational Specialist, and is a certified item writer, new teacher mentor, and Nā Kumu Alaka’i (teacher leader).

His teaching philosophy centers on mathematics a’o (teaching and learning) that honors the diverse learning processes, empowers learners to create and teach others, and prioritizes empathy in the classroom. His work has informed frameworks for equity in mathematics education and has been referenced in the Marshall Memo. Joseph is a Distinguished Modern Classrooms Educator and Expert Mentor. He also holds an M.Ed. in Instructional Leadership and a Graduate Certificate in Ethnomathematics. In 2018, he was co-awarded a Hawai‘i Innovation Fund grant for Student-led Heterogeneous Learning Communities (SHLC), an instructional routine designed to empower student leaders in semi-autonomous, collaborative classroom environments.