By Amber Strong Makaiau

A “Philosophy of Education” is not an external application of ready-made ideas to a system of practice having a radically different origin and purpose: it is only an explicit formulation of the problems of the formation of right mental and moral habitudes in respect to the difficulties of contemporary social life. The most penetrating definition of philosophy which can be given is, then, that it is the theory of education in its most general phases. – John Dewey, Democracy and Education, 1916, p. 331

Every two years I am invited to Hanahau’oli’s Kulā'iwi (multiage grades 2-3) classroom to support the students in learning more about the school’s history, progressive education philosophy, and the reasons why having a philosophy is critical to the school’s mission. This is a part of their “School Unit,” which is designed to teach the following key concepts, essential questions and instructional learner outcomes.

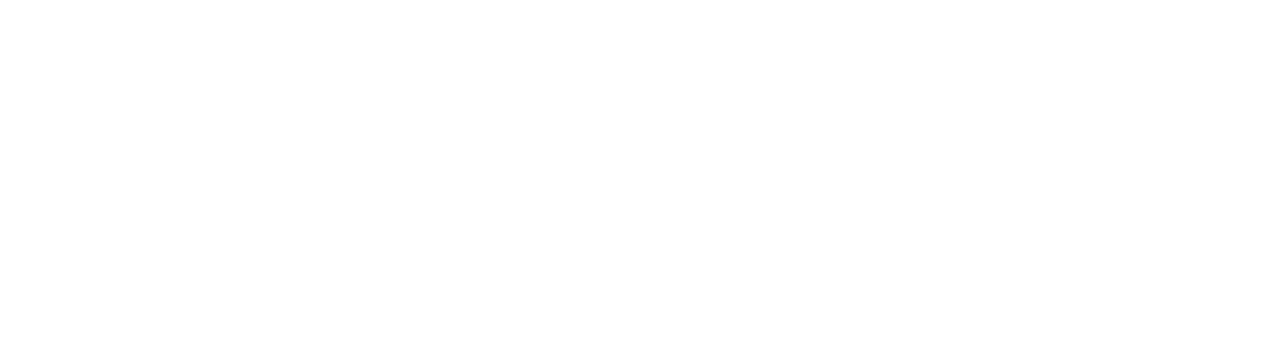

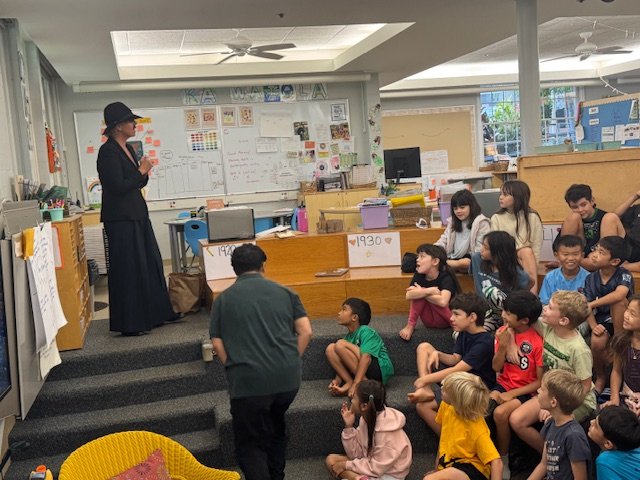

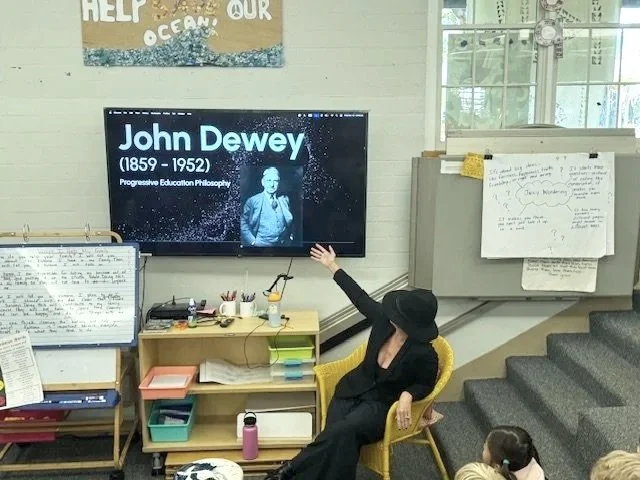

To help launch the unit I give a presentation to the whole class, sharing the history of Hanahau’oli School’s founding (see this slideshow). Guided by an abundance of questions from a very inquisitive group of seven and eight year olds, my talk includes a brief introduction to progressive education and the idea that Hanahau’oli School is grounded in a progressive philosophy of education. This plants the seeds for my return to the classroom two weeks later, when I walk in, unannounced, dressed as the ghost of John Dewey (fake mustache and all). The purpose of my second visit is to role play with the students and co-construct a deeper understanding of the school’s progressive education philosophy.

John Dewey is featured in the unit, not only because of his personal connections to Hanahau’oli School’s founding (see this previous blog to learn more about John and Alice Dewey’s connection to the school), but also because of his strong influence on rooting the larger progressive education movement within a philosophy of education, rather than a fixed teaching practice or ready-made set of educational resources. I emphasize why this distinction is important. I explain how Dewey believed that a philosophy of education (rather than a specific practice or program) can uniquely provide a framework for understanding an institution’s or individual’s core beliefs about the purpose of teaching and learning. The beliefs can be used to guide pedagogical choices, promote the critical thinking of teachers, and foster a more intentional and effective learning environment. In the words of Dewey (1916) himself, the benefits of a philosophy of education is that it:

...is an attempt to comprehend–that is, to gather together the varied details of the world and of life into a single inclusive whole…“philosophy” [is]...love of wisdom. Whenever philosophy has been taken seriously, it has always been assumed that it signified achieving a wisdom which would influence the conduct of life. Witness the fact that almost all ancient schools of philosophy were also organized ways of living, those who accepted their tenets being committed to certain distinctive modes of conduct (p.324).

With that said, he does not dismiss the important role of scientific research within the profession of teaching. He goes on to explain, “obviously it is to mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, anthropology, history, etc. that we must go, not to philosophy, to find the facts of the world…but when we ask what sort of permanent disposition of action” (p. 325) we should have about an “ongoing, changing process” (p. 325) like teaching, that is when a philosophy of education becomes the most useful and guiding source of wisdom.

Each year, as I prepare to embody the spirit of John Dewey with the Kulā'iwi students, I reflect on how critical and defining this distinct and underlying feature of progressive education really is. By being rooted in a philosophy (and not a particular practice, program, passing fad, or set of texts and materials), the school and the progressive education movement at large has been able to have an enduring and consistent through line spanning multiple generations of teachers and students. Additionally, the open-ended nature of the “wisdom” that grounds progressive education philosophy, has provided the flexibility and adaptability needed for the school and movement to respond to the changing world, diverse teaching contexts and locations, and it has helped progressive education schools evolve over time.

So what are the fundamental beliefs that define a progressive philosophy of education? A number of great thinkers have shaped the answer to this question, including those who preceded the progressive education movement like John Amos Comenius (1592-1679), John Locke (1632 - 1704), Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712 - 1778), Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746 - 1827), and Friedrich Froebel (1782 - 1852) as well as those who defined it like Francis Parker (1837 - 1902), John Dewey (1859 - 1952), Jane Addams (1860 - 1935), Maria Montessori (1870 - 1952), Caroline Pratt (1867 - 1954), William Kilpatrick Heard (1871 - 1965), and Lucy Sprauge Mitchell (1878 - 1967). And while each of these philosophers and thought leaders have had slightly different ways of describing and ultimately contributing to the evolution of a progressive philosophy of education, as Alfie Kohn put it (2015) “despite such variations, there are enough elements on which most of us can agree so that a common core of progressive education emerges” (p.2). Therefore, in my own efforts to summarize a progressive philosophy of education to the second and third graders in Hanahau’oli School’s Kulā'iwi classroom, to follow is the list of defining features that I’ve come up with. They are also listed in this slideshow that I share with the students during the ghost of John Dewey’s classroom visit.

Progressive education philosophy is grounded in the following wisdoms (and probably more):

Each human is in a unique (and similar) process of growing and becoming. Humans are not static. They are in a continuous state of change, growth, and development throughout their lives. Infants, toddlers, children, adolescents, and adults pass through distinct scientifically predictable stages of psychological, cognitive, physical, moral, and (according to some theories) spiritual development, but not always in the same way or at a similar rate. Different ages and stages require different forms and modes of learning. Teaching must be learner-centered and differentiated to meet the unique qualities and special needs of each individual. Educators who keep an open mind about each students' particular capabilities and future potential, foster ongoing growth in students.

Learning that engages the whole human is meaningful and long-lasting. Attention to the development of the whole child, not just academics is critical. Unlike machines, human learning is an embodied experience; the body is not separate from the mind but is integral to cognition, emotion, and perception. “Learning by doing” leads to deeper comprehension and retention, motivation and engagement, the ability to transfer skills, and integrate new knowledge into what we already know. Students must be given opportunities to engage with multiple disciplines (e.g. art, science, math, music, history, etc.) and modalities of learning (e.g. visual, auditory, reading, writing, kinesthetic, etc.) in both isolated and interdisciplinary ways. For learning to be long-lasting, schools should actively engage all aspects of the human experience: physical, social, emotional, cognitive and spiritual.

Experience is the greatest teacher. Schools that rely solely on ready-made curriculum, texts, drilling isolated skills and techniques, and rote memorization fail to create long-lasting learning. When all of our senses are engaged in discerning knowledge and information about the world directly through experience, deeper and more impactful understanding occurs, compared to learning something second hand. Reflection on experience–at school, home, in the community, or the natural world–solidifies learning. Some learning experiences can be designed, others require educators seizing the teachable moment and making the most of the opportunities of present life. The world is constantly changing, if schools focus on static aims and materials they miss out on authentic engagement and assessment of what students know and are able to do.

Freedom of expression, creativity, and the pursuit of genuine interests leads to human flourishing. Beyond mere survival, happiness or getting a good job–one of the highest aims of education is helping humans thrive. This includes supporting each individual in finding and fulfilling their purpose in life. Teachers who support students in identifying genuine interests and developing their capacity for self-direction and initiative, cultivate individuals who know what motivates them and drives their ongoing desire to learn. Impositions “from above,” rewards, and punishments can be quick-fixes and easy motivators in the classroom. But if learning is to be lifelong, freedom to develop naturally, self-expression, and creativity must be a regular part of the school day. This includes learning how to think for oneself and how to think in different ways. This is different from going to school to be filled with pre-determined knowledge. Through work and play –humans can discover and experience the joy of learning.

The process of living–thinking, problem-solving, working, and playing with others–teaches us how to live well together. Humans are social and we learn by constructing knowledge with others. Students must be given opportunities to contribute to and share in the community life of the school. Humans who think, problem-solve, work and play together learn how to adjust themselves as individuals to serve the interests of the group. Cooperation, collaboration, and the chance to belong to a strong and caring community help to create empathetic, justice-oriented, and thoughtful members of society. Civility, moral courage, and interest in social causes learned in school form the bedrock of a healthy, functioning democratic society.

Educators are scientists, artists, guides and co-constructors of knowledge. Teaching requires a scientific approach, drawing on research and evidence-based practices to inform instructional decisions. Teacher scientists observe, engage in inquiry, experiment, and reflect on their practice. The art of teaching lies in the creative, intuitive, and human aspects that cannot be reduced to a formula. Teacher artists must use their imagination, connect with empathy, be present, and often perform for their students. As a guide, teachers facilitate exploration, nurture curiosity, and provide support. They respond to the inquiries and questions of students with curiosity and nurture organic growth, rather than lead students to pre-designated destinations. Teachers construct knowledge alongside students by collaborating, valuing diverse perspectives, being culturally responsive, and integrating the lived experiences of children as important sources of knowledge and springboards for learning.

Schools can be powerful levers of change for creating a better future world. “As a society becomes more enlightened, it realizes that it is responsible not to transmit and conserve the whole of its existing achievements, but only such as make for a better future society. The school is its chief agency for the accomplishment of this end” (Dewey, 1916, p. 20). This idea, that schools can be powerful levers of change for creating a better future world is at the heart of the American progressive education movement. Optimism is key, as well as the belief that societies are constantly evolving–both intellectually and morally–to become more worthy, lovely, and harmonious. Integral to this process are schools, and therefore schools must evolve too. As a mini-society, the school should manifest and embody what life in an ideal democratic community looks and feels like. Students who experience this firsthand are equipped to become the full expression of their unique individual selves and contribute to the common good.

Important insert: progressive education philosophy falls under the umbrella of pragmatism. Pragmatist philosophy is a tradition that views knowledge, truth, and language as tools for solving problems and taking action, emphasizing practical consequences and experiences over abstract theoretical ideas. As a result progressive education philosophy is highly dependent on each educator’s unique ability to critically use it as a tool for interpreting, influencing, and guiding their teaching practice. In sum, progressive education philosophy is not a standalone answer or turnkey approach to what makes quality teaching. It requires the good judgement of teachers who must actively think about how it can be blended with their unique teaching style and appropriately applied to diverse school contexts, cultures, and particular moments in time.

In Democracy and Education (1916), Dewey proposes the idea that “...philosophy [can be] defined as the generalized theory of education. Philosophy [is]...a form of thinking, which like all thinking, finds its origin in what is uncertain in the subject matter of experience, which aims to locate the nature of the perplexity and frame hypotheses for its clearing up to be tested in action” (p. 331). He calls on us to ask, what would happen if every child had the opportunity to cultivate their philosophical thinking as a part of their educational experience? To expand he shares, “any person who is open-minded and sensitive to new perceptions, and who has concentration and responsibility in connecting them has, in so far, a philosophic disposition” (p. 325). He asks us to wonder, why wouldn’t we want all humans to develop philosophical dispositions as a part of schooling? To conclude, he writes that an important “characteristic of philosophy is a power to learn, or to extract meaning, from…experience and to embody what is learned in an ability to go on learning…to penetrate to deeper levels of meaning–to go below the surface and find out the connections of any event or object, and to keep at it” (p. 325-326). He makes it apparent that at the heart of his progressive philosophy of education is philosophy itself. He believed that all of us–teachers, students, parents, and ultimately society–are philosophers and that the activity of philosophy is essential to meaningful teaching and learning. This is Dewey’s wisdom, which continues to be passed down from generation to generation at Hanahau’oli School.

Works Cited:

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. Macmillan.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dr. Amber Strong Makaiau is a Specialist at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Director of Curriculum and Research at the Uehiro Academy for Philosophy and Ethics in Education, Director of the Hanahau‘oli School Professional Development Center, and Co-Director of the Progressive Philosophy and Pedagogy MEd Interdisciplinary Education, Curriculum Studies program. A former Hawai‘i State Department of Education high school social studies teacher, her work in education is focused around promoting a more just and equitable democracy for today’s children. Dr. Makaiau lives in Honolulu where she enjoys spending time in the ocean with her husband and two children.