By Amber Strong Makaiau

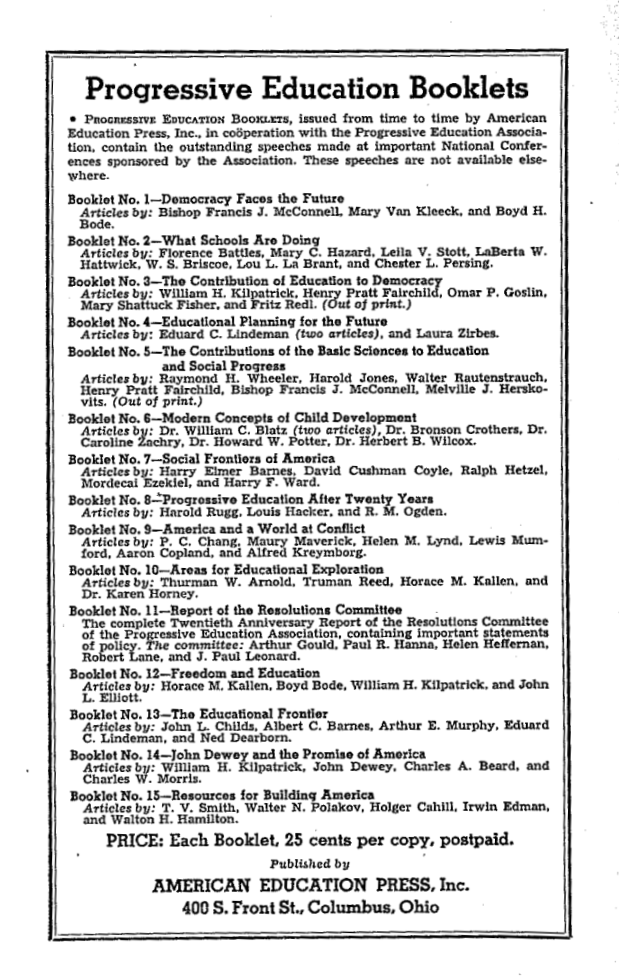

To wrap up my Summer 2025 blog series featuring a number of speeches given at Progressive Education Association (PEA) annual meetings held in the late 1930s, I present complete electronic scans of the booklets to all who find mutual excitement and curiosity about learning from the progressive education movement’s history. For those of you who missed my first blog in this series, I stumbled upon the PEA booklets during a trip to the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Hamilton Library. Nestled on the same shelf as another book I was looking for lay a stack of eight delicate publications titled, “PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION BOOKLET: PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION ASSOCIATION”. Inside each issue, the publisher noted:

The speeches contained in this booklet were taken down in stenotype as delivered by the speakers at the National Conference of the Progressive Education Association in [city, dates]… They were then edited and submitted to the speakers for their approval before publication. In the effort to place this report of the meeting in the hands of subscribers as soon as possible, only those changes necessary to make clear the meaning of the speakers were made. This fact will account for any apparent imperfections of style that may appear in the printed form of the speeches.

As far as I can tell, I’m the first person to ever check out the booklets from Hamilton Library!

Over the course of this summer, it has been so much fun reading through the speeches presented by the variety of lecturers selected to speak at the conferences. They are educators, medical doctors, psychologists, government officials, philosophers, artists, and a Bishop–some well-known, and others more obscure. They represent the diverse array of voices and perspectives that have been instrumental in making the progressive education movement dynamic and responsive to a changing world. They constitute a variety of disciplinary backgrounds (e.g. the humanities, natural sciences, etc.), helping to illustrate why progressive education is considered both an art and a science. Above all, the themes and concepts found throughout the speeches–democracy, freedom, experiential learning, critical thinking, collaboration, and social responsibility–are just as relevant and enduring now as they were in the 1930s.

While I’m not yet done sifting through the valuable insights and brilliance captured in the booklets, I’m eager to share this treasure trove via an electronic folder we made that contains a scan of each of the 44 speeches contained in the nine PEA booklets housed in the UHM Hamilton collection. Thanks to UHM Uehiro Academy student assistant, Robert Yos, you can access them all here: Progressive Education Association (PEA) booklets containing speeches given at a handful of the annual meetings of the organization in the 1930s.

In addition to this overarching folder, I present direct links to each of the eight booklets, along with a short summary of the overarching topics and issues contained in each unique publication.

1937 PEA Booklet No.1 Democracy Faces Future

The first in the series, the three speeches in this booklet focus on the progressive education movement’s commitment to perpetuating democratic governance. The authors highlight the ways in which “democracy is tied up closely with common interests, common purposes, [and] cooperation” (p. 23), exploring the role of schools in being “organized as to embody and exemplify…what a democracy should be” (p. 26). The speeches also address threats to democracy in the 1930s: dictatorships in Europe, war, attacks on free speech, propaganda, a lack of common sense and agency in individuals to positively impact their world, and lack of imagination about the potential of science to create cooperative communities.

1937 PEA Booklet No. 2 What Schools Are Doing

This set of speeches was organized by the PEA Committee on Experimental Schools. The duty of this committee was to keep members “in touch, through voluntary reports received from schools, [regarding] the progress of progressive theory and practice throughout the country” (p.5). At the time of the 1937 National Conference, the committee had received reports from 78 schools and school systems, 44 of them public and 34 private. The speeches highlight a number of ways that progressive education philosophy was being translated into practice in schools in the 1930s.

1937 PEA Booklet No. 3 The Contribution of Education to Democracy

The one thing that all of the speeches contained in this booklet have in common is that they focus on the role of education in a democratic society. The initial speech titled “The Contribution of Education Toward the Improvement of Democratic Living” (pp. 5-10) was written by William Kilpatrick, one of the most influential progressive educators at the time, credited with coining the term “project-based” learning. This particular booklet highlights the central role that democracy plays in the purpose of a progressive education.

1937 PEA Booklet No. 4 Educational Planning for the Future

The speeches contained in this booklet all focus on the progressive education tradition’s commitment to promoting social responsibility in educators, students and communities. The opening pages of a lecture given by Laura Zerbes from Ohio State University summarizes this collection well: “We had no notion of making this just another conference. We did not think of it even as a mere matter of reporting on what we had done, but rather as an intelligent opportunity, an opportunity that could be intelligent with reference to the getting together of group movements, an opportunity for the clarification of issues that are confronting us individually and that are beyond our individual grasp” (p.15).

1937 PEA Booklet No. 5 Contributions of the Basic Sciences to Education Social Progress

Progressive educators are interested in the ways in which schools can support “social progress.” The speeches contained in this booklet draw from psychology, biology, the physical sciences, social work, religion, and anthropology – wondering how each of these fields of study can uniquely inform educators as they work to improve the lives of individuals and communities.

1938 PEA Booklet No. 6 Modern Concepts of Child Development

Progressive educators place a strong emphasis on understanding and fostering child development as the foundation for effective learning. They view children as active agents in their own learning, rather than passive recipients of information, and focus on nurturing their intellectual, social, emotional, and physical growth. The speeches contained in this booklet aim to illuminate how knowledge of child development–propagated by pediatricians, educational researchers and psychologists–can support the work of progressive educators.

1938 PEA Booklet No. 7 Social Frontiers of America

One of the key tenets of progressive education is the ability to respond to a changing world, and as a result, teachers and administrators need to study societal trends, data, and future forecasting. This set of booklets aims to “describe the United States right now” (p. 5) so that progressive educators of the era would have a better understanding of their current world. The speeches cover a wide range of topics from industry, government, and the fragility of democracy on the eve of World War Two.

1938 PEA Booklet No. 10 Areas for Educational Exploration

Similar to the speeches contained in previous booklets, this series of lectures names the societal changes of the era and hypothesizes how progressive educators can use schools as sites for supporting youth as they navigate uncertainty and rapid transformation. They address larger concepts like freedom, propaganda, and capitalism. They focus on the needs of the youth as a group (or generation) as well as individual well-being and personality development.

1939 PEA Booklet No. 15 Resources for Building America

The speeches contained in this booklet were delivered at the National Meeting in celebration of the eightieth birthday of John Dewey. The conference took place in New York City. In addition to addressing a number of important elements of progressive education–democracy, the creation of a better future society, and arts integration for example-each of the speeches also include personal anecdotes and stories about the impact of John Dewey on their professional lives.

Finally, I’m sharing one more cool scan that we made. This additional, larger PEA booklet was also on the shelf in Hamilton. It is titled, “Progressive Education Association Evaluation in the Eight Year Study.” In a previous blog, I shared how the Eight-Year Study was a massive evaluation sponsored by the PEA between 1933 and 1941. To examine the impact of progressive education on student learning, this experimental study compared students who attended progressive schools with those in more traditional programs. The results of the research found that students from the experimental progressive schools performed as well as, or better than, students from traditional schools on standardized tests. The progressive education students also outperformed their counterparts in traditional schools in areas like problem-solving and creativity. They demonstrated greater engagement in artistic, social, and political activities and the students in the most experimental (progressive) schools showed the most significant gains. The document I’m sharing with you today (and linked below) contains a series of specialized reports about the Eight Year Study that the PEA distributed to their subscribers.

The Progressive Education Association Evaluation Reports of the Eight Year Study (Full Manuscript)

The PEA evaluation reports of the Eight Year Study contained in this booklet are:

Bulletin No. 1 (1935) Anecdotal Records: Describes the development of a technique for collecting anecdotal records, “which do help effectively in the education of students.”

Bulletin No. 2 (1935) Evaluation in Mathematics: Is "addressed primarily to teachers of mathematics” to inform and improve their practice.

Bulletin No. 3 (1935) Interpretation of Data: Provides evidence of “the ability of students to use the scientific method, teachers in the thirty schools devoted considerable time to that aspect called ‘the interpretation of data’... and this bulletin contains a description of the objective as conceived by the cooperating teachers.”

Bulletin No. 4 (1936) Evaluation of Reading: Written for teachers interested in the evaluation of reading in an effort to develop a “cooperative attack on the problems associated with the interpretation of reading records.”

Bulletin No. 5 (1936) Application of Principles: “Teachers in the Thirty Schools have expressed a desire several times to receive information about the techniques for making tests which attempt to measure aspects of thinking. A procedure for evaluating the ability of students to apply facts, definitions and principles to new situations is described in this bulletin.”

Bulletin No. 6 (1936) Social Sensitivity: This is a report of the “exploratory study of social sensitivity sent to each committee member.” It is authored by Hilda Taba who pioneered a concept-based approach to teaching that emphasized inductive thinking and student-centered learning.

It is my hope that the dissemination of these historical documents will support the work of progressive educators today. This sentiment is captured in an 'ōlelo no'eau (Hawaiian proverb) that states: I ka wā ma mua, ka wā ma hope. The translation from Hawaiian to English references the relationship we all have to the time in front and the time in back of us (Ching, 2003). It is the idea that the future is in the past. Kameʻeleihiwa (1992) elaborates, "it is as if the Hawaiian stands firmly in the present, with his back to the future, and his eyes fixed upon the past, seeking historical answers for present-day dilemmas" (Kameʻeleihiwa, 1992, p.22). Grounded in this wisdom and the deep understanding that our history has much to teach us about our lived experiences in the modern-era, may we all find solutions to today’s challenges by looking to the past as a guide to the future.

…and if any of the speeches resonate with you, and you are compelled to write about your own reflections inspired by these pieces, please don’t hesitate to contact us with your ideas for a future blog!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dr. Amber Strong Makaiau is a Specialist at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Director of Curriculum and Research at the Uehiro Academy for Philosophy and Ethics in Education, Director of the Hanahau‘oli School Professional Development Center, and Co-Director of the Progressive Philosophy and Pedagogy MEd Interdisciplinary Education, Curriculum Studies program. A former Hawai‘i State Department of Education high school social studies teacher, her work in education is focused around promoting a more just and equitable democracy for today’s children. Dr. Makaiau lives in Honolulu where she enjoys spending time in the ocean with her husband and two children.